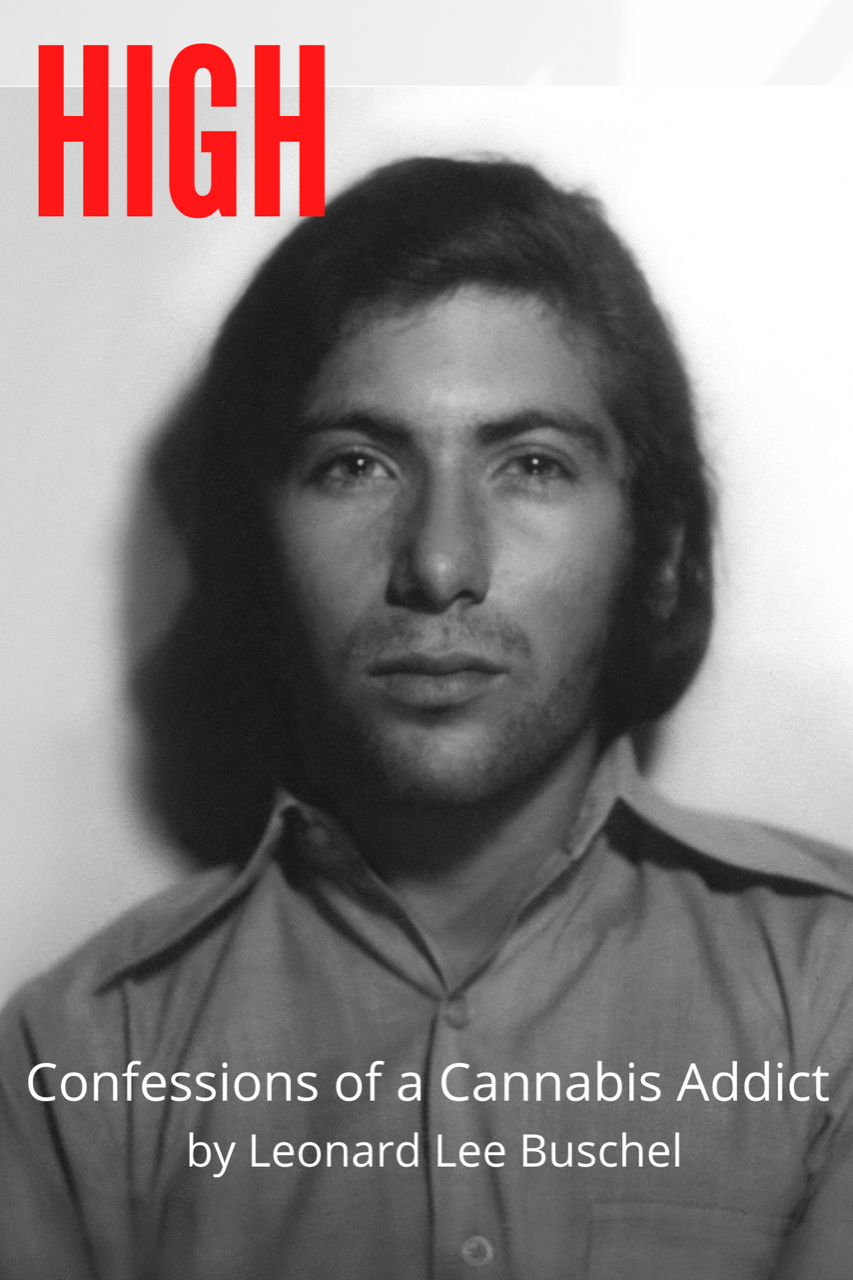

This week we bring you Chapter 1 of HIGH Confessions of a Cannabis Addict By Leonard Lee Buschel. Leonard Lee Buschel is an American publisher, substance abuse counselor and co-founder of Writers in Treatment, which supports recovery and the arts, and executive director of REEL Recovery Film Festival, focusing on stories of addiction and recovery. This week, we bring you the Preface to whet your appetite. Follow us weekly for more delicious chapters of this incredible story.

Chapter 1

Grief like a torn dress should be left at home

I am not what happened to me, I am what I choose to become.

—Carl Jung

OPENING MONTAGE: Camera descends through the delicious mists above a pot of simmering chicken soup at 4639 N. 10th Street—the house where I grew up. There I am, having just been born into an idyllic Jewish family unit smack-dab in the middle of the twentieth century, with a working father, a beautiful, house-wifey mother, and a strong handsome three-year-old brother. I started life in the North Philadelphia neighborhood called Logan, in a row house with mortgage payments my parents considered affordable.

When Mom and Dad brought home their bouncing baby boy from St. Joseph’s hospital, my mother pressed her tender ear to my tiny chest and heard a heartbeat that was anything but regular.

The next day my mom called the delivery doctor and told him she’d heard something strange when she put her ear to my chest. The doctor had already detected a loud murmur associated with a bicuspid aortic valve disorder. The doctor didn’t want to tell my parents right away about my defective heart and ruin the family’s first night home with their new beautiful baby boy.

There was an operation available to repair said defect, but in the 1950s, 1 out of every 10 kids who went under the knife to repair the errant valve never made it back home to watch Howdy Doody.

In those days, there was no heart-lung machine. The surgeon would have had only three-and-a-half minutes to replace the little piece of shit valve in my heart. Mom was not about to play Beat the Clock with a life-threatening experimental surgery. But she was willing to bet that operating room technology would advance faster than my valve’s health would retreat. Mom was certainly right on that estimation.

Three weeks after I took center stage, my daddy dropped dead of a heart attack on his way home from working the night shift at the post office. He was 34 years old. Suddenly there was a gaping hole in our lives. No husband, no father, no breadwinner.

Mom was a grief-stricken and frightened widow. Shock prevented her from breastfeeding, so at three weeks old, my first bartender eighty-sixed me. Mom had no job and the mortgage became unaffordable. She was now confronted with a new reality: How was she to have the time to raise my brother and me into men when she needed to get a nine-to-five job? How would a 100 percent woman manage to raise two sons without a father around? Could her instinct and intuition carry her through? The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care by Dr. Spock was not in her library.

I was a particularly large drain on family emotions. Before I could even walk, I was faced not only with a life-threatening heart condition but with a gnarly breathtaking case of severe asthma, which ultimately led to numerous emergency room visits.

My lucky brother’s life started with daddy’s gentle masculine push. Over the years, I’ve seen 8 mm home movies of my brother Bruce, being pushed by my father on a swing and another home movie shows him being held above the cresting waves in the Atlantic Ocean off Atlantic City by the proud, strong hands of our daddy. Others called him Morris. I called him deceased.

For my brother, our father’s death was much more of a loss than it was for me. I’m sure on an unconscious level, I must have been devastated. Though at the time I probably didn’t notice, being so focused on Mom’s fountains for youth. Who was going to hunt for food, gather wood, and keep our row home supplied with heating oil to stay warm at night? At three weeks old, I had to metaphorically stand on my own two feet while actually only able to lie on my back or stomach, as newborns do. I was already starting a new chapter in my life, as I did again 44 years later when I got sober. It’s not like I was on one uninterrupted trajectory from infancy to the Betty Ford Center. I did stop at nursery school, public schools, weddings, fatherhood and racetracks. But at three weeks old, without realizing it, I was pretty much faced with having to fend for myself.

Being brought up by a single mom is like being an electrical plug with only one prong. The energy is not a balanced flow. A missing father is a missing prong. A missing father short-circuits a child’s learned response to stimuli. As a man, he may overreact to everyday problems as if he were from Venus and not from Mars.

How would I learn the aplomb a father uses to smoothly carve a holiday turkey? Or repaint the bedroom or change a flat tire? I would never know how to safely experience the fear and unsteadiness that come when Daddy takes off the training wheels to unleash the careen of the bike on the asphalt. Or feel his love, assistance, acceptance and protection at the same time. When I had my own son, I told him the first thing to learn when riding a bike is how to fall over (on a grass field), and the second thing is how to get up and keep pedaling. Somehow, I managed to master this life lesson without a daddy of my own.

When I started to attend elementary school, I heard kids in the playground talk about their fathers and the jobs they did. I would slink away embarrassed that I didn’t even have a father. Heretofore, I never really knew what I did not have. I did have some older guys in the neighborhood who took me under their wings from time to time but never like a father would.

One of the best realities of my life was that my family lived in the same house for 20 years. I felt secure in the Brigadoon-like neighborhood of Logan in North Philadelphia. I say Brigadoon because to me Logan was like the mythical village in Scotland that rose out of the Scottish mist once every 100 years, for only one day of joy and splendor.

Logan, built on top of a buried creek, existed as a middle-class Jewish ghetto for about 50 years, before three square blocks (including my house) sank into the mud, disappearing off the face of the earth forever. There is no old block to go back to visit. Except through memories, and in family photos, 10th Street will remain forever a shimmering universe of childhood adventures and fantasies. And where my creation story started off with a death and a wheeze.

My mother, Rose, only drove a car twice in her life; once for a lesson and then to get her driver’s license. She really didn’t need one because she usually only travelled with her boyfriends or took public transport. We never owned a car. As a kid, the only modes of transportation I ever knew were buses and subways, walking, riding my bike, and hitchhiking. I hitchhiked to Olney High School every day for three years. When I was late, the teachers understood that I didn’t get a ride fast enough to be on time.

I grew up self-reliant, with two bus stops a block from my house and with only a 20-minute walk to the Broad Street subway. Our station was the Wyoming Avenue stop. From here, for a five-cent token, I could travel up and down the spine of this city of neighborhoods or to where the Declaration of Independence was birthed and to the home of comedian W. C. Fields. One story has it that Fields had the following words engraved on his tombstone at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California: “All things being equal, I’d rather be here than in Philadelphia.”

School was a challenge to my developing ego. I attended a big school that had three floors and two elevators. My heart problem, a bicuspid aortic valve that should have been tricuspid, got me a special elevator pass (like a seat on the “special” bus).

I was never allowed to participate in the regular gym class, so I took remedial gym where the only equipment was a Ping-Pong table. And there wasn’t always someone to play against. I became bored with boredom.

My special pass to use the elevator was necessary all winter, when my ridiculously bad asthma caused me to wheeze like an out-of-pitch accordion. That wheeze embarrassed me greatly. I didn’t want the other kids to know I had any physical defects, so I would wait for everyone to go into their classrooms before I slipped into the elevator. Self-stigmatization. If a guy saw me and asked what I was doing taking the cripple’s elevator (kids are cruel)—because they all saw me playing basketball and other ball games at lunch and recess—I would make up a story (lie).

I got along with pretty much everyone in the neighborhood, a skill that would eventually help get me through some of life’s biggest challenges. Luckily I was born in the Chinese year of the chameleon.

I grew up playing sports on neighborhood streets every day and was able to do more than my doctor advised. The rules for street games weren’t set like in Little League. The guys would have to renegotiate the rules and boundaries every day. One day, first base was the black Chevy, second base was the old Fairlane, and third base was the blue Caddy. We debated every little disagreement but not for long. We wanted to get on with the game.

Whatever game we were playing became the most important thing in our otherwise dull lives. Physical exertion and competition made us feel more alive than any homework assignment or family chore. We knew our dream game would be cut short when someone’s mother called them in for dinner, or the darkening sky would call the game.

The first time I needed emergency medical attention was at age 10 in Rockaway Beach, a neighborhood in Queens, New York. Almost dying in Rockaway Beach prior to puberty is a depressing and enervating concept, especially for someone whose entire life consisted of just one decade.

The cast of characters leading up to my potential last gasp consisted of Mom, Brother Bruce and the relatives we were visiting on December 25 to celebrate the birth of that famous Jewish stuntman who is probably rolling over in his grave because he didn’t get credit for teaching Houdini everything he knew. Uncle Larry, Jewish, married Mary, Catholic and very Italian. Aunt Molly, the spinster, was there too. So were Larry and Mary’s two sons, both real rednecks.

Much like the Three Wise Men arriving at the manger, we three managed to make it to Rockaway Beach, with Mom and Brother Bruce carrying the gifts. I arrived with a deadly cat allergy—a “gift” I would have gladly returned with no refund. Italian Aunt Mary and Uncle Larry had two cats. I don’t remember their names, but I will always think of them as Sacco and Vanzetti. Except these little fuckers were guilty.

I’m sure my aunt and uncle didn’t acquire them with nephew-murder in mind, but as we sat down to an authentic Italian feast, my breathing became somewhat labored, short and difficult. Wheezing is what it’s called. Mine was louder than a cat’s purring.

Not one to draw attention to myself, I refrained from mentioning my lack of oxygen for as long as possible, until I was compelled to rasp out, “Mom, I’m having an asthma attack.”

“Relax,” she whispered to me, “just try to get through dinner.”

By now, my wheeze was quite audible, and they all probably heard me, even if their gazes never lifted from the authentic homemade lasagna on their plates. “Relax,” Mom said. Relax my ass. I wasn’t having a fucking anxiety attack. I was having a cat-dander-provoked major asthma attack.

Not a hard time breathing. Not breathing.

Mom didn’t want to be embarrassed by her little Lee, not after being so embarrassed losing her husband 10 years before. After all, hadn’t we taken the train from Philly to New York, the subway all the way from Penn Station to Far Rockaway, and hadn’t our relatives bestowed upon us a duffle bag full of Christmas gifts? Ironically, the gift I most needed was a new pair of lungs, but I wasn’t holding my breath.

I told her again, which wasn’t necessary because my wheezing was now louder than the Mario Lanza album on the Victrola. Eventually, I was given the only ingestible remedy at that time: a noxious slime of liquid. Aminophylline in a vulgar-tasting pink colloidal cocktail. The taste always made me gag and occasionally, throw up. An even more unpleasant intervention was my mother giving me Aminophylline suppositories. To this day, that’s why I’m only comfortable with fingers in my ass and never cocks or dildos.

I kept the vile medicine down and was taken to my Aunt Molly’s apartment nearby to wait for the wheezing to diminish. All through the night, I had to sit up and fight for every breath. In retrospect, I think that if someone, such as a loving family member, had gently rubbed my back and put their warm soothing hands on my shoulders, the breathing would have calmed down.

Such was not the case. Swedish massage or the laying on of hands were not among my family’s established healing practices. Many Jewish families don’t touch. For the Hassidic, they are afraid a woman might be on the menstruation cloth, and a man might have Hep C. This is perhaps a cultural trait. Indians put their hands together and say namaste. The Japanese don’t shake hands. They bow to your aura. The Jews don’t bow to your aura. They just ignore it altogether.

Mom and Aunt Molly waited till sunrise to make an emergency call to Molly’s general practitioner because no one should bother a doctor in the middle of the night. Arriving in his obligatory Buick, black bag in hand, the good doctor whipped out his somewhat sterilized reusable syringe, filled it with adrenaline, and poked it into my arm.

I’m sure it hurt, but I was too busy struggling for my next shallow breath to notice the pain. Within minutes, I was out of danger and suddenly aware of the three facts leading to one unasked question. The three facts: (1) the black-and-white television was on; (2) I was very hungry; and (3) I could breathe again. The unspoken question: “Why the hell didn’t any of you take me to the emergency room?” I think I knew the answer. It was bad enough to bother a doctor in the evening and even worse to inconvenience an entire hospital.

Asthma was my constant companion. The fear of an attack was especially elevated during special occasions. I was 10 when Brother Bruce had his Bar Mitzvah. Mom wanted to make sure Brother Bruce and I knew how to dance for the occasion, so she hired a very attractive, tall, buxom instructress to teach her little men to cha-cha. I think the big hit at that time was Moon River by Henry Mancini.

Brother Bruce and his face stood exactly chest high to the big-breasted dance teacher. It was in that well-cushioned environment that he experienced the reality of erections. Weeks later, when he finally intoned, “Today I am a man,” it was true with intention, if not in consummation. I made it through the Bar Mitzvah and the cha-cha sessions without becoming breathless—a glorious accomplishment in those days.

Not breathing is also exceptionally inconvenient and potentially life threatening. Oxygen deprivation is known to cause irreparable brain damage and can lead to erratic and bizarre behavior. I am still capable of both with a perfectly healthy brain.

A few years later, while playing touch football in the street, I had to quit the game because I was having an asthma attack. My brother got pissed off because the game had to stop until a new player showed up. What Brother Bruce didn’t know was that wheezing might be hellish and scary, but I really didn’t want to take that truly vile pink shit, the Aminophylline, with its ammoniacal odor and a bitter taste.

Shortly thereafter, a miracle of modern medicine occurred. Our family physician, Dr. Doodies, made a house call to see about the heavy wheezing. Sitting next to me on the sofa, he reached into his black bag like a magician with his hat. Instead of pulling out a live rabbit, he pulled out one of the first albuterol asthma rescue inhalers in America.

My life changed forever when my doctor gave me that inhaler.

“Hold it in your hand and press here and breath in, then do it once more,” he said with the confidence of a confidence man.

I pressed it in and breathed in as deeply as I could and then did it again. Thirty seconds later, I wanted to get back into the game—the game of football and the game of life. The attack stopped on a dime. It was a miracle. It saved my life, many times, and gave me a mobility I would have never had if I needed to be rushed to a hospital for every difficult bout of wheezing. However, as I was perpetually abusing myself with pot and coke, the Ventolin inhaler didn’t always work. As it is, I have been 911’ed and ambulance driven to ERs about a dozen times in my life. After all, take away someone’s breath and what do you have? A corpse.

I can easily sum up my youth. Defects of the heart, problems of the lungs. That sentence fragment, although grammatically incorrect, is absolutely true in characterizing my life. It wasn’t until a little later that compulsive gambling became my favorite problem.

#

Growing up my home routine was just that—very routine. Every day, Mom went to work, and I went to school. After school, I was alone for a few hours, and if I couldn’t find a ball game to join, I would set fires, steal things, shoot sparrows in the backyard with my dead father’s .22 single shot Remington rifle, hang out at Cooper’s (the corner candy store) or watch TV. The shrinks call that acting out. I called it solving loneliness, boredom and existential angst.

When I was 12, I was addicted to Classics Illustrated comic books, such as Moby Dick, Treasure Island, and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and they were my constant companions. While Mom thought I was sleeping in the next room, I was actually counting Robinson Crusoe’s footprints in the sand or wondering whether Captain Nemo was still 20,000 leagues under the sea.

My favorite day was Tuesday, not for the television shows that were airing but because that’s when the TV Guide came in the mail. It was like receiving a new lease on life every week. Other people’s lives to watch every day. My life was focused on TV, what was on, and what was on next. I would underline (no highlighters back then) all the shows I didn’t want to miss, like an executive whose entire life is chiseled in their day planner. The TV Guide listed all the TV shows I wanted to watch and couldn’t live without.

On cold winter afternoons, The Three Stooges, Boris and Natasha, and Sally Starr were my only companions. One day, many years later, I turned on the TV and had a neurobiological revelation. Just as the TV was starting up, making its usual crackling sounds, I could feel my brain turning off, see my brain cells diming, shutting down thoughts and feelings, suddenly stuck in time, like in suspended animation.

Looking back, I realize that every time I came home to an empty house after school and turned on the television, it helped assuage my burgeoning youthful existential angst. I didn’t feel so alone. Of course, all these shows were interrupted every 10 minutes by commercials. Childhood brainwashing. In 2013, children saw an average of 40,000 commercials a year, and many more if you include the Internet and social media. If you see enough advertisements, you eventually stop existing as an original human being. You are now no longer you. Now, I try not to have the TV on. My fear was that, when I die, it won’t be my life passing before my eyes but Jerry Seinfield’s.

In 1965, when I was 14, my mother took me to the Locust Street Theatre (on Locust Street) for a matinee performance of The Roar of the Greasepaint—The Smell of the Crowd, by Anthony Newley and Leslie Bricusse. Much of the cast was my age, except for the leads.

This singular stage show helped me to understand love, politics, hope, oppression, war and nonviolence all in one afternoon. At 14, I was just waking up to politics. John Kennedy was offed just the year before. I agreed with Dallas D.A. Jim Garrison and didn’t think the assassination was just the efforts of a lone lunatic with the best aim ever.

The show’s dramatically powerful portrayal in music was one of those magical experiences I have not forgotten to this day. Resembling a music hall production more than a sit-com style musical, the plot examines the maintenance of the status quo between the upper and lower classes of British society in the 1960s. My 10-second summary boils down to this: The play is about the tension and class disparity between two characters—a rich man and a pauper, Sir and Cocky, the oppressor and the oppressed. It was an allegorical plot with characters named for who and what they are; Sally Smith played the Kid, the Girl was played by Joyce Jillson, the Negro was Gilbert Price, where he introduced the world to the classic of classic songs, Feeling Good, recorded by dozens of artists but made most famous by Nina Simone.

When I realized that Anthony Newley wrote the show, composed the music, and lyrics (with Leslie Bricusse), directed the production, sang, danced and acted in it, my admiration for him was set forever. Years later, my friend Jesse Jones worked for Mr. Newley as his personal concierge. Jesse told me that after Newley’s divorce from Joan Collins (yes, the Joan Collins of film, TV and theater fame), his entire tour entourage consisted of only one person—his mother. This, I could relate to. Jesse also assured me that Mr. Newley was the sweet and classy gentleman I imagined him to be. This brilliant artist and perfect gentleman died on April 14, 1999.

All of the shows that I had seen before had many set changes. When I realized the set of The Roar of the Greasepaint, The Smell of the Crowd was not going to change, I was focused on every aspect of the production. Anthony Newley, Cyril Richard, and Gilbert Price gave performances that blew my 14-year-old mind. The memory remains so fresh that listening to the original cast recording still moves me to tears.

I had the pleasure of introducing my son Ben to the score by playing “A Wonderful Day Like Today” on many mornings before school. Once I came home to find Ben listening to the CD on his own. I was proud and happy that I could pass something on to him that meant so much to me. And I don’t even think he was getting high yet. And he wasn’t going gay. If I had caught him listening to “Cabaret” or “Funny Girl,” I may have thought otherwise.

In sixth grade, my homeroom teacher, Mrs. Forman, brought in a record player one day and put on “In the Hall of the Mountain King,” from the Peer Gynt Suite. I was moved in a way that Sinatra (the most listened-to artist at home) never did move me. I could feel dormant parts of my little brain start to come alive. I also felt my heart skip a beat, in a good way. My teacher told us about a place called Norway. Never heard that word as Mom didn’t sit around the dinner table discussing Scandinavia. I ended up loving Björk.

Mrs. Forman put on “Morning Mood” from the same suite. I needed to hide my face because I didn’t want my girlfriend, Jeanette Jekel, to see me cry. Hearing the two superb musical masterpieces exposed me to the alpha and omega of emotions that classical music inspires. (Facebook, being what it is, I sent this chapter to an old friend from the same elementary school I attended to see if she had similar memories of Mrs. Forman’s class. She sent back this note. I will let it speak for itself: “I hope you include in your memoir that Arlene Marinoff sat behind you in sixth grade and scratched your back with a ruler in exchange for pictures of Ben Casey and Dr. Kildare that your mom got from Perfect Photo. I would have done it for free as I had a crush on you. You were adorable.”)

A similar experience happened 10 years later, in 1969. I was with Brother Bruce, in his Opel Kadett, a fairly nondescript vehicle. It takes some living to know what kind of car you should be wearing. For years I drove a Volvo. The automobile most favored by pot dealers. Big trunk, low profile. No cop ever stopped a professor in his Volvo mistaking him for a pimp or drug dealer.

Brother Bruce and I decided to use the East River Drive to get home. We were cruising along the Schuylkill River when Brother Bruce turned on Temple University’s full-time jazz station, WRTI. What was about to happen in that Opel Kadett was anything but nondescript. The song that came on was like a psalm, a chant, a prayer, a beseeching voice, like a shot of caffeine that percolated into a frightening cacophony. We drove home in silence and sobs for exactly 37 minutes, until we parked in front of our row house on 10th Street. The music? It was “The Creator Has a Master Plan” by Pharoah Sanders and vocals by Leon Thomas. You probably think I was high? No shit. I was high every single day of my life from the age of 18 to 44. But the piece sounds as good today sober as it did 50 years ago. I’m listening to it right now, not high, not stoned, just in tears. It’s about the horrors of slavery . . . freedom and enlightenment.

Years later I would often see Mr. Sanders hanging out in various jazz clubs around San Francisco. It was like having royalty in the room. His countenance was truly regal. It was as if on that afternoon in 1969, God came down and gave unto me the world of jazz, a world that makes life worth living. Although really good jazz makes you feel as if you might be dying.

Before music CDs, we collected vinyl discs. There were 45 rpm (revolutions per minute) singles, and 33 1/3 rpm long-playing albums—LP for short. I ordered my first 33 1/3 rpm record player when Columbia House advertised a very special offer in a magazine: a real stereo, long-playing record machine with detachable, extendible speakers, plus six “free albums,” for only $14.99.

Being a bit flippant, I ordered it without asking Mother whether it was okay, because she was after all going to get the bill when the stereo arrived. Which reminds me of a story told by Marie-Louise von Franz sometime in the ‘80s, a story that has guided me all through my life ever since. She tells about a friend on the subway platform in Prague, looking down and seeing a lot of cigarette butts. Feeling like lighting up herself, the woman asks the nearby station master if it’s okay to smoke there. The station master responds very emphatically, “No, it is VERBOTEN.”

“What about all these butts?”

“They didn’t ask.”

So I got an Andy Williams LP, some Frank Sinatra (we share a birthday, 12/12), and the Dave Brubeck Quartet’s Time Out, which included the jazz standard “Take Five.” Also, the life-changing Judy at Carnegie Hall. Maybe I was gay after all. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that! Thank you, Jerry Seinfeld.)

Soon after I received the LPs, I traded The Andy Williams Christmas Album for an LP by someone named Bob Dylan. Brother Bruce got very angry because he had never heard of Bob Dylan, and he loved The Andy Williams Show. Then Brother Bruce smokes his first joint while listening to the Dylan LP. Moved to such intense emotions never felt before, Brother Bruce went into the basement and masturbated.

If Mr. Dylan (a.k.a. Robert Zimmerman) reads this, I hope he takes Brother Bruce’s response as a compliment. Lord only knows how Brother Bruce handled himself after accepting Dylan as the troubadour of our generation.

#

I don’t ever remember doing any homework on my own volition. I did as little homework as possible, just enough to get C’s. That’s because A’s didn’t matter much to my mother. She was more concerned with me being street smart than school smart, like she was.

At the end of a long day at work, Mom would come home and prepare dinner. She had a very special way of lifting the foil off the Swanson TV dinners. We ended the evening watching TV and eating Breyers vanilla fudge ice cream. In fact, I had a horrible sugar habit. (It’s only a moderate problem now.) I would buy cases of Coca-Cola with my own money and drink up to six small bottles a day. They were only a little more than a dime each. Sugar. The cheapest antidepressant on the planet.

I was one of the only kids in the neighborhood with a charge account to go into the corner grocery store and get whatever I needed—or wanted. I could also do that at Jack Parrish, a classy men’s apparel store. I never abused the privilege. I knew we only had the money my mother earned at Perfect Photo, a photo-finishing plant, where I got my first job in the eighth grade. Looking back, I’m sure my strong independent decision-making powers came from those shopping experiences without Mom.

When Mom sent my brother (age seven) to boarding school, I felt like an only child. Really, I was a lonely child. Brother Bruce would come home for the weekend every Saturday morning. I would be waiting for his bus at the corner, unless he called to tell us he was in trouble at school and not allowed his weekend pass. Sadly, that happened a lot.

When the Number 75 bus rolled down the street, my anticipation would be gleeful or painful. Because when the door swung open, Brother Bruce wasn’t always on the bus. So, I would wait, almost in a trance, another 20 minutes for the next one. When he finally arrived, the weekend began, like the beginning of a great buddy movie. That’s how I learned to love waiting. The anticipation was so delicious I was in heaven, not thinking about anything mundane, knowing my Jesus had arrived again. We would play sports, fight with each other, pal around, and go to the movies. On Sundays, the bus that delivered him would take him away.

When Brother Bruce wasn’t visiting or on the 75 bus, he was at a boarding school/orphanage called Girard College. Founded in 1833 and opened on January 1, 1848, Girard College was created by provisions in the will of Stephen Girard, the fourth richest man in America at that time. He saved the U.S. government from financial collapse (loan shark?) during the war of 1812. He also envisioned a school for “fatherless and poor white boys.” Yep, that was the Buschel boys.

Girard wanted to educate boys who might otherwise be lost, whose mothers would be forced into prostitution or waitressing, to prepare them for useful, productive lives. I was exempt from this heartfelt act of ego-driven and racist social generosity because I had a loud heart murmur only spoken of in quiet whispers. Exempt isn’t the right word. Rejected is more accurate.

They didn’t want me there, and my brother didn’t want me to go there. At the time, I did not know why. He later said he wanted to spare me the unpleasant (horrible) experience, which he revealed in his memoir, Walking Broad, 2007.

Brother Bruce advised our mother not to send me (for my own good).

It’s highly likely that the officials at Girard feared that I wouldn’t withstand the nightly buggering that so traumatized my elder brother. He later spent a small fortune on Freudian therapy—good money on bad memories.

Girard’s painful initiations into the world of unwanted intrusions allegedly softened considerably and withdrew completely when this educational facility went coed in 1984. The anticipation of midnight rides having nothing to do with Paul Revere are, as far as we know, no longer a concern.

But I was desperate to be near my brother. And family members made Girard College sound like an excellent opportunity to get a fine education at a private school, at no cost! I did not go to that hideous place but instead hit the Oedipus jackpot. I got to stay home with Mom, watch TV, eat Breyers ice cream, and hang out at Cooper’s candy store.

Still, on weekends when the fatherless boys’ orphanage kept Brother Bruce grounded for some infraction, and kept him from coming home for the weekend, my boredom would set in. At around 10:00 a.m. I’d start looking for something to do or for trouble to get into. One noncompetitive game I played was called step ball. Sort of the equivalent to solitaire. It wasn’t a very complicated game. The player (me) would throw a rubber ball against a flight of steps and then the other player (me) would catch it in the air. Over and over and over. It was like having a catch with yourself.

One of my favorite escapes was to go to the cinema. I lived within walking distance of three movie theaters, and I was at one of them at least once a week. When I heard about Saturday matinee double features (and I could cross the street by myself), I walked there to be immersed in three hours of total stimulation and escapism.

Sometimes, a friend and I would go for the Saturday matinee and then afterward hide in the balcony playing gin rummy and parsing out Raisinets to sustain us until the evening features. We saved money by not paying another admission fee and enjoyed watching the more sophisticated films at night meant for adults. Those were some of the happiest days of my life.

The correlation between happiness and cinema is forever linked in my consciousness. The first movie theaters were referred to as “dream palaces” not only for their ornate architecture but for the altered state achieved by patrons for five cents. I learned to love the movies, except the time my mom took me to see Psycho (child abuse), and it scared the crap out of me.

A mama’s boy, one competition for my mother’s affection had died and the other was packed off to boarding school. Father dead . . . brother excommunicated . . . and she was all mine. For years it made me a very possessive and jealous lover. For years? Bullshit! Forever.

1 Comment

WHEN I SMOKED WEED I HAD A MILLION FRIENDS,AS AN ALKIE I ENDED UP WITH NONE,JUST ME AND THE BOTTLE.I FEEL A MID LIFE CRISIS COMING ON I THINK I START SMOKING AGAIN. I SMOKED FOR YEARS AND QUIT CAUSE I WENT WITH A GIRL WHO LOVED TO DRINK AT CLUBS AND DID NOT LIKE MY SMOKING.QUITTING WEED WAS THE WORST THING I EVER DID.ALCOHOL IS A HORRIBLE RIDE, THGE LOST JOBS,TOTALED CARS, POLICE PROBLEMS, NOT GETTING ALONG WITH ANYONE INCLUDING HER, ETC, ALL BAD.

WEED IS HARMLESS REALLY I COULD GET HIGH IN THE AFTERNOON SOBER UP AND GO OUT THAT NIGHT LIKE I HAD NEVER SMOKED.IF I DRINK ALCOHOL IN THE AFTERNOON I AM DONE FOR THE DAY AND PROBABLY TOMORROW ,TOO.