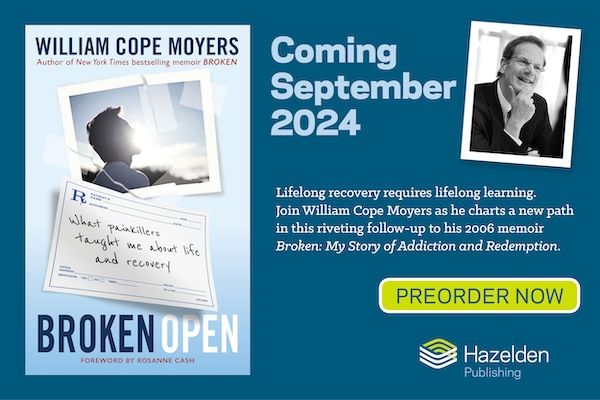

William didn’t know something was missing until it happened. He’d been in recovery for alcohol and drugs for years. He was a recovery activist and a spokesperson for the gold standard of treatment and recovery organizations. He was a model leader and follower of Twelve Step programs. But, still, he slipped. And his slip lasted a few years. Privately, he was addicted to painkillers while publicly saying he was in recovery from alcohol and drug use. So, was he still in recovery? How could this happen to someone who did everything ‘right’? How did it go so wrong? With brutal honesty and introspection, William shares what happened after sobriety – after he’d published his candid and shocking memoir, Broken, in 2007.

William didn’t know something was missing until it happened. He’d been in recovery for alcohol and drugs for years. He was a recovery activist and a spokesperson for the gold standard of treatment and recovery organizations. He was a model leader and follower of Twelve Step programs. But, still, he slipped. And his slip lasted a few years. Privately, he was addicted to painkillers while publicly saying he was in recovery from alcohol and drug use. So, was he still in recovery? How could this happen to someone who did everything ‘right’? How did it go so wrong? With brutal honesty and introspection, William shares what happened after sobriety – after he’d published his candid and shocking memoir, Broken, in 2007.

*********************************************************

There was a time—pretty much the entire 1980s—when I didn’t do much good in the world. It’s not that I didn’t have opportunities. My upbringing and education, my family’s connections, and my natural talents positioned me to be a contributing member of society. My addictions got in the way, however. My inability to consume alcohol like “normal” people—which means knowing when and how to stop drinking—and my insatiable pursuit of the released-from-reality high I experienced from smoking everything from marijuana to crack cocaine never seemed to affect my pleasant manners, but it certainly put a crimp in my capacity for reliably decent citizenship. It also destroyed dozens of personal and professional relationships, cost me my first marriage, and derailed what might have been a satisfying and productive career in journalism.

My addictions not only prevented me from doing good things; they also induced me to do bad ones. It’s difficult to overstate the shame that addicts and alcoholics like me hold on to because of who we became and what we did under the influence of the substances or behaviors that dismantled our wills and directed our actions. We lied and stole. We wasted energy and opportunities and resources. We spent money we didn’t have and made promises we wouldn’t keep. We manipulated others with excuses and evasions. We hurt our loved ones and ourselves and then tried to convince everyone that it didn’t matter. Waking up to the reality of these failures is painful, and confessing them is often an agony, no matter how compassionate or kind the person who finally hears us out.

These feelings might fade beneath the grace of forgiveness or be admitted and amended via processes like the Twelve Steps, but most of us continue to carry a sense of obligation that doesn’t go away even with the passage of time. We, who for so long were useless to many of the people who loved us or needed us or wanted to rely on us, want to be useful. We want to somehow make right what was wrong. For many of us, myself included, fulfilling this desire to make good what we once made so bad becomes a part of the way we stick with recovery; sometimes it leads us to jobs and careers in professions that help or heal.

In their book Beyond the Influence, my friend and confidant Kathy Ketcham and her coauthor William Asbury write eloquently about the crisis that feeds this impulse among many recovering people.

“If you are an alcoholic, during your drinking days you only took in; if you are like most alcoholics, you took everything you could get from anyone who was willing to give it to you. Rarely did you give anything back. The anguished insight that so much was taken and so little was given in return is the source of the alcoholic’s most profound spiritual distress.

The most difficult spiritual work in recovery is to understand that the source of your anguish is not the desire to get back what you have lost, but to give back what you have taken.”

If my work at Hazelden offered me an opportunity to pay back the debt I owed to the miracle of recovery, Broken provided a kind of vocational promotion. The book’s popularity with readers and the attention it got from the media gave me a new and bigger way to be useful. My story of addiction connected me to millions of other stories that shared its familiar and destructive shape, even if our details were different. My story of redemption offered these people some hope that they, too, could get better. Through Broken I became part of the solution for people who were still suffering with active addictions or slogging through the early months of recovery as well as those who loved them. Publishing and promoting the book opened the door to people who wanted my help and gave me a way to connect with and help others. What I shared with the world seemed to matter. It seemed to make a difference. It seemed to meet a need.

Even during my first attempts at treatment, when I desperately wanted to believe how different I was from the junkies and drunks around me, I sensed that sitting with others who were in the same boat was significant. Eventually I realized that this kind of connection and fellowship was also a reliable way for me to stay sober. Focusing on someone else’s struggle pulled me out of self-pity and navel-gazing. Being useful—even to one other person—affirmed that I was worthwhile. And it distracted me from my search for other things that might make me feel better. I was persuaded by the “one alcoholic helping another” simplicity of AA. We can’t recover in isolation. When we try, we will nearly always fail. This insight continues to guide and shape my recovery, and it is a core part of the healing and hopeful message I help the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation share with the wider world.

I wish I could say that the self-serving/other-serving generosity of the Twelfth Step was the sole reason I wrote a memoir and got it published, but I’m not that kind of saint. I had a desire—a need—to help others. I also wanted to be famous. My early life had given me a taste for celebrity—completely un-earned by me—and my career since getting sober had put me somewhere on that map, this time for my own sake. I liked the way audiences responded to my speeches and presentations. I was gratified when journalists called me for comments or had me as a guest on their shows. Being a player in the corridors of power and a public representative of a noble cause made me feel good. My hunger for the kind of respect and admiration my father has achieved and enjoyed through his storied career has always been part of what drives me. The expectation that I live up to my name and my potential was stitched into my psyche from my earliest days and has dogged me for decades. Insecurity about my ability to do this—to measure up—colors my life and influences my choices to this day.

Because it was a story that could help others in need, Broken was an act of service. To borrow the metaphor from Beyond the Influence, it was payment toward the debt I owed for the gift of recovery. Because it became a bestseller, the book also gave me a place in the sun. Its critical and commercial success, and the attention it drew to me as a person, offered hope that I might finally break out from beneath my father’s long shadow and achieve the rewards of recognition and regard and approval that would satisfy my own deep need to feel like I mattered. As I tried to keep all the pieces of myself and my life together during the years my marriage was falling apart, these twined impulses continued to work in me, sometimes for the better and often for the worse.